Problems with peanuts, in a nutshell

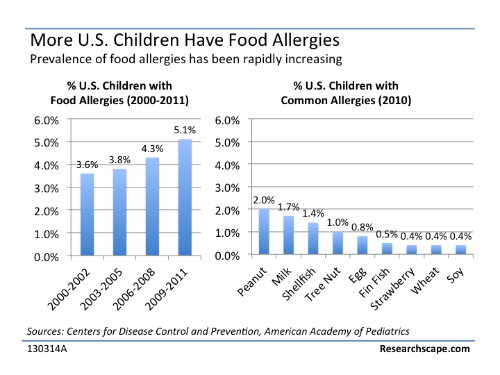

The peanuts contained a toxin-producing fungus called Aspergillus flavus, from which the name, aflatoxin, comes. New research suggests that peanut allergy in children has increased 21 percent since 2010, and that nearly 2.5 percent of US children may have an allergy to peanuts.1

Aflatoxins are found not only in peanuts, but also in many other foods, including corn, milk, eggs, meat, nuts, almonds, figs and spices. In fact, corn may be the crop with the greatest risk worldwide, because it’s grown year-round in climates ideal for fungal growth; it’s also a staple food in many countries. Cottonseed is another crop that poses a high risk of fungal contamination. Aflatoxins are also sometimes detected in milk, cheese, eggs and meat when animals ingest contaminated feed.

A few years ago, Consumers Union looked into the question of aflatoxins 2 in peanut butter and found that the amounts detectable varied from brand to brand. The lowest amounts were found in the big supermarket brands such as Peter Pan, Jif and Skippy. The highest levels were found in peanut butter ground fresh in health food stores.

Health Effects of Peanut Aflatoxins

Aflatoxins are labeled as a human carcinogens that have been found to cause liver cancer in animals and humans, according to the Environmental Health Trust website. Severe aflatoxin poisoning has been reported in many poor countries around the world. Acute aflatoxicosis, the syndrome resulting from exposure to aflatoxins, is characterized by vomiting, abdominal pain, pulmonary edema, convulsions, coma and death, notes the Cornell University website.

The U.S. government tests crops for aflatoxin and doesn’t permit them to be used for human or animal food if they contain levels over 20 parts per billion. While we don’t know much about the dangers of long-term exposure to low levels of aflatoxin, my colleague Kathleen Johnson, a dietician here at the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine, points out that there hasn’t been an outbreak of liver cancer among U.S. kids, who as you know, consume enormous amounts of peanut butter.

Aflatoxins are not considered a problem in the United States, according to the Berkeley Wellness website. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration allows low levels of aflatoxins in foods because it considers them as unavoidable contaminants. In many developing countries, aflatoxins pose a more serious risk, but in the United States, peanuts, peanut butter and other foods that may contain aflatoxins undergo rigorous testing. FDA guidelines allow no more than 20 ppb, or parts per billion, of aflatoxin in human foods. Still, there is concern about the possible long-term effects of low-level aflatoxin contamination. You can limit your exposure by purchasing peanuts and peanut butter from large, brand name manufacturers and by discarding any moldy, shriveled or discolored nuts, notes MedlinePlus./

Causes of exponentially increased allergens

VACCINES: Could Peanut oil in vaccines triggers autoimmune response to peanuts?

The real shame, though, is the history of peanut allergy itself. In her new book The Hi?story of the Peanut Allergy Epidemic, Heather Fraser explains how peanut allergy has its roots in mass vaccinations foisted on the general public by the very same industry that is now trying to profit from treating it.

Vaccines have long been known to trigger anaphylaxis — this is the basic premise, after all, behind how they work — bearing evidence that they are, in fact, the primary cause of many food allergies. In the case of peanut oil, refined versions that may still contain peanut proteins are still being injected into children, in many cases triggering an allergic reaction to the food itself.

“Peanut is an excellent adjuvant as it is potentially highly allergenic and therefore very good at priming the immune system — although its use must also risk not just priming the immune system but sensitizing it,” explains Foods Matter.

“Although it was little publicized, the medical profession had always been aware that vaccination by injection carried the risk of inducing allergy but, as in the early days of cow pus vaccination and serum sickness, the risk was felt to be outweighed by the benefits.”

GMOS: Could the presence of GMO increase food allergens?

The huge jump in childhood food allergies in the US is in the news often[1], but most reports fail to consider a link to a recent radical change in America’s diet. Beginning in 1996, bacteria, virus and other genes have been artificially inserted to the DNA of soy, corn, cottonseed and canola plants. These unlabeled genetically modified (GM) foods carry a risk of triggering life-threatening allergic reactions, and evidence collected over the past decade now suggests that they are contributing to higher allergy rates.

Food safety tests are inadequate to protect public health

Scientists have long known that GM crops might cause allergies. But there are no tests to prove in advance that a GM crop is safe.[2] That’s because people aren’t usually allergic to a food until they have eaten it several times. “The only definitive test for allergies,” according to former FDA microbiologist Louis Pribyl, “is human consumption by affected peoples, which can have ethical considerations.”[3] And it is the ethical considerations of feeding unlabeled, high-risk GM crops to unknowing consumers that has many people up in arms.

HERBICIDES: Could increased herbicides on GM crops may cause reactions?

By 2004, farmers used an estimated 86% more herbicide on GM soy fields compared to non-GM.[9] The higher levels of herbicide residue in GM soy might cause health problems. In fact, many of the symptoms identified in the UK soy allergy study are among those related to glyphosate exposure. [The allergy study identified irritable bowel syndrome, digestion problems, chronic fatigue, headaches, lethargy, and skin complaints, including acne and eczema, all related to soy consumption. Symptoms of glyphosate exposure include nausea, headaches, lethargy, skin rashes, and burning or itchy skin. It is also possible that glyphosate’s breakdown product AMPA, which accumulates in GM soybeans after each spray, might contribute to allergies.]

read more about GMOs and herbicides and their possible impact on our children’s allergens at http://www.responsibletechnology.org

RESOURCES;

1. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/10/171027085541.htm

2. drweil.com

3. You can learn more about peanut allergy and vaccines here:FoodsMatter.com.

4. GMOs and allergens http://www.responsibletechnology.org